An Acoustic Neuroma or Vestibular Schwannoma is a brain tumor that actually grows on the balance nerve. Because of that, most folks with an Acoustic Neuroma diagnosis have some kind of impact on their balance. Everyone’s experience is unique to their situation, but this is the story of my balance.

I have always been a clumsy person. When I went through that big growth spurt in puberty, everyone said that I would get used to my new proportions, but I never really got my spatial awareness down. I have funny stories about the time I managed to somehow fall off a stationary bike or when I went paddleboarding and just randomly fell into the lake.

Approximately nine months or so before I was diagnosed with a brain tumor, I started experiencing mild dizzy spells. These dizzy spells typically didn’t last very long and were always accompanied by a headache. My general practitioner recommended that I just take headache medicine when it happened and see if the dizziness went away – which it did, so I didn’t think much of it.

But around that time, I went to the chiropractor for an adjustment, and after she adjusted my neck, I became so dizzy I had to spend the rest of the day prone on the couch. Thankfully, the next day was more normal. I made a point of asking her to be more gentle for adjustments after that, using the tool instead of her hands to adjust, and I did not have that problem again.

I had gotten orthotic inserts in my shoes to help with a bunion, and I was finding it harder to balance, especially on one foot, during exercise classes – which I thought was because I was adjusting to my inserts. I kept thinking it would improve given time to acclimate.

In retrospect, all of these were signs of the tumor that I didn’t recognize.

When I was diagnosed with my 3cm Acoustic Neuroma, the doctors had me undergo a battery of neurological and vestibular tests. They said that I had done a very good job of compensating for my compromised balance nerve. I was surprised how balance tests worked – I expected to walk in a straight line or something similar. Instead, they primarily measured my eyes and eye movement because eyes are an important part of the balance system. The craziest test was when they shot cold water in my ears and measured my eye movements in goggles. In my healthy ear, the cold water test made me feel like I was on a roller coaster, even though I was laying flat on a table. In the tumor side ear, I felt nothing except the cold temperature.

When I woke up after my nine hour brain surgery, I was extremely motion sick and nauseated – which is common after a surgery where they cut the balance nerve. I threw up a lot. It didn’t matter if I closed my eyes; my brain was very confused about what was happening in my vestibular system.

Once the first night passed, the hospital staff got me up and walking. To start with, I was quite tippy. I remember the physical therapist asked me to stand on a pillow, and I had to be caught because I immediately started falling over. Within a couple of days at the hospital, I was able to walk slow, careful laps around the Neuro ICU. (Nothing makes you feel like a rockstar like walking in the Neuro ICU and having all the nurses clap when you go past their station.) Physical therapy worked with me every day, and I had to really focus hard to rebuild those memorized pathways of how balance worked. But I was walking unassisted when I was discharged.

My care team discharged me straight into vestibular physical therapy. I started the week I left the hospital. I honestly cannot recommend it enough, specifically vestibular therapy. My therapist was wonderful, helping me work toward goals I wanted to achieve for my life. Again, many exercises focused on my vision, like looking in one spot and turning my head. After I got down the exercise in a well lit space, the therapist would challenge me by dimming the light.

I really wanted to get back to riding a bicycle, as it is an important form of recreation for me – and also my most common method of transportation to work. By the time I was discharged from therapy, I was able to ride my bicycle again.

Healing from something as large as a brain surgery takes a lot of time. There was a lot of effort and work my brain had to put into relearning balance. I felt that I was healing for about 18 months after my surgery. During that time, I continued actively working on my balance and stretching myself. Just like muscle mass, if you don’t use it, you lose it. I recognized that balance is critical for the rest of my life, so I wanted to keep my balance as robust as possible. I slowly worked my way up, adding difficulty like I had learned in vestibular therapy. I was back doing modified versions of exercise like Zumba 8-10 weeks after surgery. About a year after my surgery, I achieved a huge goal: riding my bicycle in the dark with a headlight. Before my surgery, I regularly biked home from work in the dark, and I really wanted that option again. It felt like freedom to get that back.

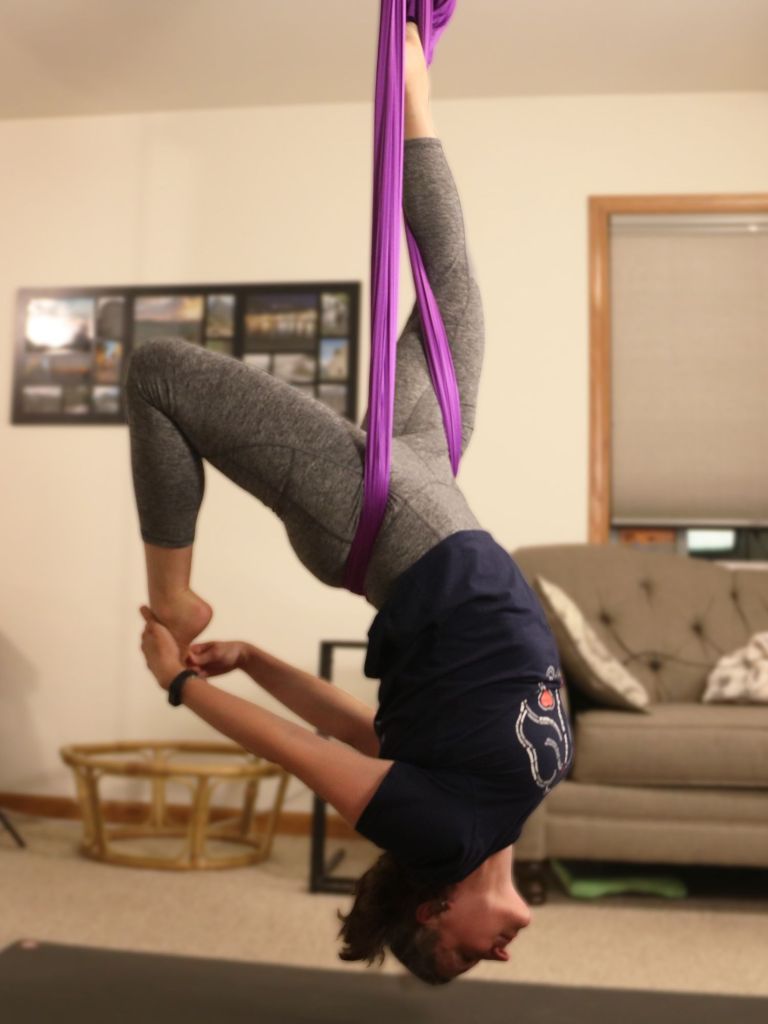

These days, I continue to work my balance to grow my strength and skill, but also I am cautious. I do yoga regularly (including aerial and paddleboard yoga), roller blade, cycle, ice skate, cross country ski, hike, Zumba, kayak, etc. I am careful to plan and make sure conditions are optimal- especially that there is sufficient light for any activities that may challenge me. I always wear protective gear (helmets, knee pads, life jackets, etc.). I also pick and choose my balance challenges. My husband usually handles things like cleaning the gutters, as tasks like grabbing while on a ladder are really hard for me. If I do use a ladder, I make sure to set it up to be as safe as possible. I don’t have stairs in my home, which I love, but when I do carry things on stairs, I am extra careful. I skip things that I know my balance cannot handle, such as strobe light areas in a haunted house. I take my time and focus hard in situations where my balance may be struggling, like walking on a boat that is pitching in the waves. I plan on my balance taking energy, and I know that when I am tired, I will be much more clumsy. I also expect that I will have a harder time in the dark. I baby step my way up from simpler to more complicated balance tasks, building up. I have learned too that ‘new to me’ is always harder for my balance, even if the balance seems easier than other challenges I have faced. Familiarity makes a big difference in my ability to balance.

An anecdote of where my balance is at now that I am nine years post surgery: the other evening, I attended an impromptu ice skating event. We went ice skating on a pond in the woods. I had to traverse up and down a wooded hill in the dark with a headlamp. After the woods, I crossed a marsh to get to the ice. The party happened in the evening, so it was dark, but the ice was illuminated with a handful of lights. After skating within the lights, I tested if I could go outside the lights and skate just with my headlamp. I was pleasantly surprised to find that I could – though I would not have won any speed races. I thoroughly enjoyed the evening. but when I got home, I was absolutely exhausted.

These days, I very rarely have dizzy spells. Dizziness almost exclusively occurs when I am sick, like a sinus infection or extra bad congestion. I have to continue to be careful in situations like uneven surfaces or in the dark. In general, balance takes energy and focus, and if my brain is very occupied with other tasks I am likely to trip or stumble. I can always tell I am overtired when my clumsiness spikes dramatically. However, with some accommodation and preparation, I can generally do the things I want to do.

Leave a comment